[tweetmeme source=”Life_With_DID”]

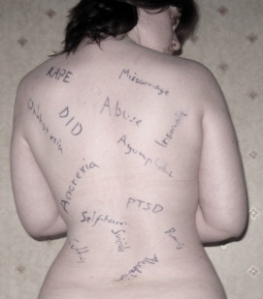

I’m very passionate about mental health and abuse awareness, mainly due to my own expieriances. I am very open about my past, which I know is something that many do not like, but I do not see why I should stay silent – afterall that’s what the abusers told me to do and I can’t let them win can I?

I don’t want nor do I expect pity or sympathy. I do not deserve it, and I do not want it, what happened happened and I am only who I am today because of it. I do not want hugs and people saying they are sorry, what I want, what I fight for every day, is for OTHERS to feel safe that they will not be judged. What I want is to make it so that those who currently suffer in silence scared of what may happen if they open up know that they are not alone, and maybe make it so that they no longer have to fear judgement and blame.

I know that my work and my speaking out will not end abuse, discrimination and suffering, but if I can just let people know that they are not alone and do not have to suffer in silence and maybe if I can make a few people stop and think then I am happy with that. I cannot stop abuse, I cannot change the world, but maybe I can help to plant the seeds of change, plant that idea in to the minds of others, and then they can help that idea to grow until one day change can and does occur. Maybe one day the things which I fight will no longer exist, but I doubt that I will see that day. I can do so little, but it’s the best I can do, I just have to hope that human nature is not as bad as I fear and that these seeds if change and the glimmer of hope will take root.

I tell my story, my truth, not for pity, but for the hope that I can help to ignite change in this world. I know most will not believe this, but I know my truth and I hope that a few of you know this truth too. This is why I spend so long creating websites, writting letters, speaking in schools, raising money and trying to spread awareness. It’s an inconvenient truth I know, but it’s a truth that needs to be known, I cannot just sweep it under the carpet when I know that it could help others. So I fight and strive with the hope of helping, of making the suffering of others that little bit better that bit more bearable. I wish that this truth was not there, that it did not need to be spread, but it is and it does. And for this I am sorry

This is my truth